New research shows there is a strong correlation between water fluoridation and the prevalence of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, or ADHD, in the United States.

It’s the first time that scientists have systematically studied the relationship between the behavioral disorder and fluoridation, the process wherein fluoride is added to water to prevent cavities.

The study, published in the journal Environmental Health, found that states with a higher portion of artificially fluoridated water had a higher prevalence of ADHD. This relationship held up across six different years examined. The authors, psychologists Christine Till and Ashley Malin at Toronto’s York University, looked at the prevalence of fluoridation by state in 1992 and rates of ADHD diagnoses in subsequent years.

“States in which a greater proportion of people received artificially-fluoridated water in 1992 tended to have a greater proportion of children and adolescents who received ADHD diagnoses [in later years], after controlling for socioeconomic status,” Malin says. Wealth is important to take into account because the poor are more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD, she says. After income was adjusted for, though, the link held up.

Take Delaware and Iowa, for instance. Both states have relatively low poverty rates but are heavily fluoridated; they also have high levels of ADHD, with more than one in eight kids (or 14 percent) between the ages of four and 17 diagnosed.

In the study, the scientists produced a predictive model which calculated that every one percent increase in the portion of the U.S. population drinking fluoridated water in 1992 was associated with 67,000 additional cases of ADHD 11 years later, and an additional 131,000 cases by 2011, after controlling for socioeconomic status.

“The results are plausible, and indeed meaningful,” says Dr. Philippe Grandjean, a physician and epidemiologist at Harvard University. This and other recent studies suggest that we should “reconsider the need to add fluoride to drinking water at current levels,” he adds.

Thomas Zoeller, a scientist at UMass-Amherst who studies endocrine disruptors—chemicals that interfere with the activity of the body’s hormones, something fluoride has been shown to do—says that this is “an important observation in part because it is a first-of-a-kind. Given the number of children in the U.S. exposed to fluoridation, it is important to follow this up.” Since 1992, the percentage of the U.S. population that drinks fluoridated water has increased from 56 percent to 67 percent, during which time the percentage of children with an ADHD diagnosis has increased from around seven percent to more than 11 percent, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Others felt more strongly. “The numbers of extra cases associated with a one percent increase in the 1992 artificial fluoridation [figures] are huge,” says William Hirzy, an American University researcher and former risk assessment scientist at the Environmental Protection Agency, who is also a vocal opponent of fluoridation. “In short, it clearly shows that as artificial water fluoridation increases, so does the incidence of ADHD.”

But scientists were quick to point out that this is just one study, and doesn’t prove that there is necessarily a causal link between fluoridation and ADHD. They also noted a number of important limitations: Individual fluoride exposures weren’t measured, ADHD diagnoses weren’t independently verified and there may be other unknown confounding factors that explain the link.

Dr. Benedetto Vitiello, a researcher at the National Institutes of Health, says that the link between the two may not be a causal one and could be explained by regional or cultural factors. Charles Poole, an epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina, says that this research suggests fluoride should be more carefully studied, but doesn’t show much of anything by itself. “I think the authors were quite cautious in their interpretation… and [accurate] in their statement of the study’s limitations,” he says. “So it would be ludicrous to draw a strong conclusion based on this study alone.”

Nevertheless, previous research has suggested that there may be several mechanisms by which fluoride could interfere in brain development and play a role in ADHD, says Dr. Caroline Martinez, a pediatrician and researcher at New York’s Mount Sinai Hospital.

Animal studies in the 1990s by researcher Phyllis Mullenix, at the Harvard-affiliated Forsyth Research Institute, showed that rats exposed to fluoride in the womb were much more likely to behave in a hyperactive manner later in life. This could be due to direct damage or alteration to the development of the brain. (Mullenix’s adviser told her she was “jeopardizing the financial support” of her institution by “going against what dentists and everybody have been publishing for fifty years, that [fluoride] is safe and effective,” and she was fired shortly after one of her seminal papers was accepted for publication, according to Grandjean and a book by investigative journalist Christopher Bryson called The Fluoride Deception.)

Multiple studies also suggest that kids with moderate and severe fluorosis—a staining and occasional mottling of the teeth caused by fluoride—score lower on measures of cognitive skills and IQ. According to a 2010 CDC report, a total of 41 percent of American youths ages 12 to 15 had some form of fluorosis. Another study showed structural abnormalities in aborted fetuses from women in an area of China with high naturally occurring levels of fluoride.

There have also been about 40 studies showing that children born in areas home to water with elevated levels of this chemical (higher than the concentrations used in U.S. water fluoridation) have lower-than-normal IQs. Grandjean and colleagues reviewed 27 such studies that were available in 2012, concluding that all but one of them showed a significant link; children in high fluoride areas had IQs that were, on average, seven points below those of children from areas with low concentrations of the substance.

One recent small study of fewer than 1,000 people in New Zealand suggested that water fluoridation didn’t decrease IQ. But that study had some serious errors, according to Grandjean, who writes that “a loss of 2-3 IQ points could not be excluded by their findings.” And only a small percentage of people in the study actually lived all their lives in areas without fluoridation, and even less didn’t use fluoride toothpaste, severely limiting the validity and relevance of the findings, he says.

About 90 percent of the fluoride that is added to the water takes the form not of pharmaceutical grade sodium fluoride but of a chemical called fluorosilicic acid (or a salt formed using the acid). This material is a byproduct of phosphate fertilizer manufacturing, according to the CDC. Several studies have suggested that this form of fluoride can leach lead from pipes, says Steve Patch, at UNC-Asheville. Other work shows that children in fluoridated areas have elevated blood lead levels, and fluoride may also increase the absorption of lead into the body, says Bruce Lanphear, an epidemiologist at Simon Fraser University. Lead itself is a potent neurotoxin and has been shown to play a role in ADHD, Lanphear adds.

There is also good evidence the fluoride impairs the activity of the thyroid gland, which is important for proper brain development, says Kathleen Thiessen, a senior scientist at the Oak Ridge Center for Risk Analysis, which does human health risk assessments for a variety of environmental contaminants. This could indirectly explain how the chemical could impair attentional abilities, she says.

Just last month, a study was published in the Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, which found that there were nine percent more cases of hypothyroidism, or underactive thyroid, in fluoridated versus non-fluoridated locations in England.

“Fluoride appears to fit in with a pattern of other trace elements such as lead, methylmercury, arsenic, cadmium and manganese—adverse effects of these have been documented over time at exposures previously thought to be ‘low’ and ‘safe,’” Martinez says.

Grandjean concurs, citing a 2014 study he co-authored with researcher Philip Landrigan in The Lancet that characterizes fluoride as a developmental neurotoxin. Others, like Lanphear, prefer to call the chemical a “suspected developmental neurotoxin.” One problem, he says, is that there is no formal process for determining whether or not something is toxic to the brain.

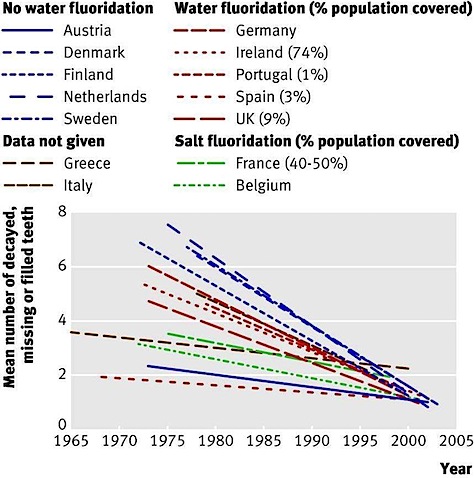

The CDC declined to comment on the study, but maintains the fluoridation is “safe and effective,” and calls fluoridation one of the “ten great public health achievements” of the twentieth century for its role in preventing tooth decay. The American Dentistry Association says that the process reduces decay rates by 25 percent. It should be noted, though, that in recent decades rates of cavities have declined by similar amounts in countries with and without fluoridation—and the United States is one of the few Western countries besides Ireland and Australia that fluoridate the water of a majority of the populace.

Limitations aside, the study suggests that there is a pressing need to do more research on the neurotoxicity of fluoride, Lanphear says. In fact, every single researcher contacted said that fluoridation should be better studied to understand its toxicity and low-dose effects on the brain. Some deemed the lack of research on the chemical concerning and surprising, given how long it’s been around—fluoride was first added to water supplies beginning after World War II.

Regarding whether or not fluoridation is a sound public health practice, he says that he “can’t make that decision for the public, but I’d certainly recommend that more studies are done, in an urgent fashion.”

Source: http://www.newsweek.com/water-fluoridation-linked-higher-adhd-rates-312748

Leave a comment